Ethnodemocracy Part 5: Zulu Blues

How the ANC has drowned opposition with municipal demarcation and infiltration

KwaZulu Natal is known for a few basic things. It is hot, green and wet, covered in sugarcane, riddled with political violence, home to the Zulus, and to what used to be the biggest Indian diaspora on earth.

It is a highly divided province, but one in which the ANC’s control is unlikely to be shaken.

This follows on form the first four parts of the series, which can be found here:

Part 1, part 2, part 3, part 4

Buried in the boroughs

Two years ago, Jacob Zuma was arrested for contempt of court, and his supporters in the MKVA launched a massive campaign to cripple the country, focusing on KZN and Gauteng, shutting down essential infrastructure for two weeks. To keep the momentum going, they destroyed retail outlets and storage depots, sending out whatsapp messages to alert people to looting opportunities.

But they also used these channels to encourage racial violence, against Whites and Indians in their homes. This attempted pogrom soon failed, as the middle class minorities turned out to be well armed and organised.

Instead of taking it lying down, or fleeing, Indians and whites took to defending their neighbourhoods with extreme determination, and have since been demonised in the press for the “Phoenix massacre” in which roughly 300 violent rioters were killed trying to kill, burn and loot their way through the Indian-majority suburb. While several black communities managed to organise resistance as well, and there was some cross-racial cooperation, Durban was, as I understand it, more racially divided in this event than Johannesburg.

The galvanising effect on the Indian population has been tremendous, and with the historical precedent of the 1949 pogrom against them, the Indian population is understandably on their guard.

The DA had a smart operator in their midst, and soon capitalised on the event by reassuring the residents that they did nothing wrong.

This was the right move, but some unconfortable conversations at the braai caused party seniors to demand Mike Waters retract his campaign. He resigned after this.

This was not the first moment that the Indian population had begun to entertain a touch of racial consciousness. For a long time in the post-apartheid era, they voted in significant numbers for the Minority Front party, which managed to eke out two parliamentary seats.

But they were divided between three parties - the ANC, who had fought for their equal rights, the DA, who promised clean, competent and nonracial governance, and the MF, who promised to look after their ethnic interests. The ANC support collapsed in the 2014 elections, moving to the DA after ANC representatives told them that if they didn’t like ANC rule they should bugger off back to India.

Nevertheless, the opportunity for pushing the ANC under 50%, a trend driven in part by the EFF splitting the vote, and in part by the increasing voter apathy among black voters, has given new impetus to minority bloc voting drives. In particular, the new Employment Equity guidelines, which drastically cut the maximum allowable minority employment proportions, even to zero for some provinces, have given the grip the DA needs to increase voter participation.

But avenues to remedy their situation politically are unfortunately quite limited. Aside from the persistent black racial bloc majority discussed in the first part of this series, there is also a rather firm barrier to achieving any local autonomy in the province.

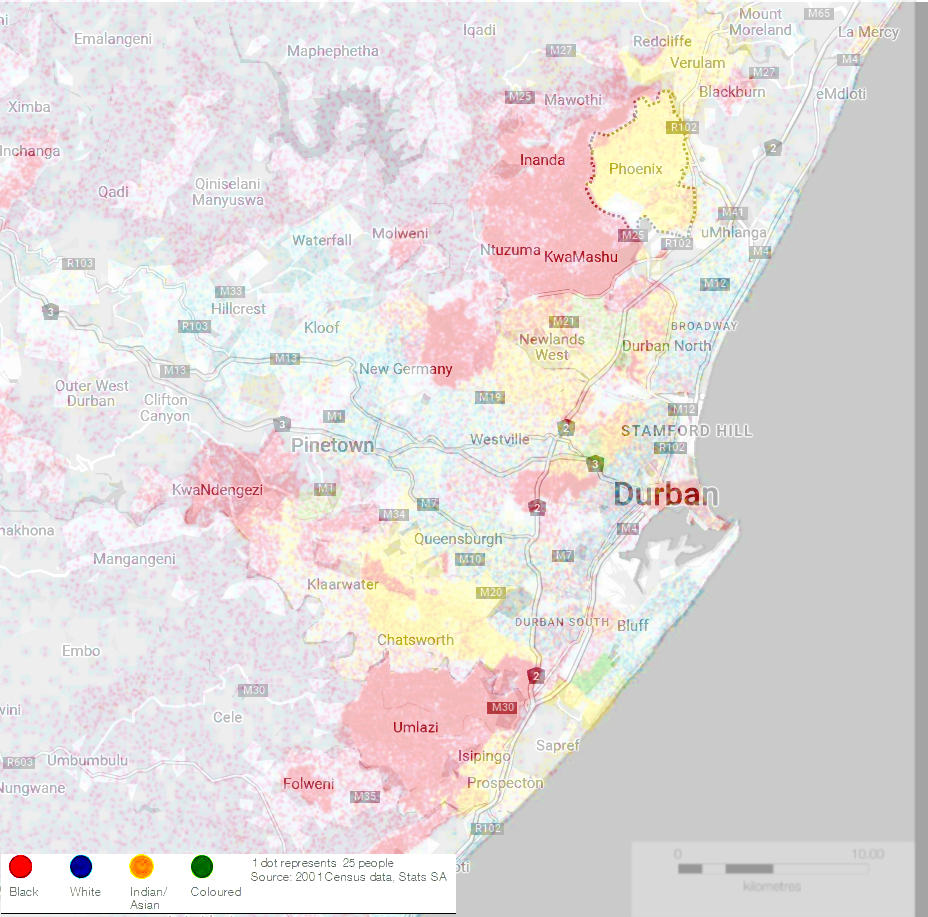

For the maps below, I superimposed Adrian Frith’s 2011 census data dotmaps over a greyscale map of the city. Phoenix has a dotted highlight. It’s not very clear, but what should be noticeable if you squint, is the extent to which the white and coloured areas are not only less densely populated (old suburban plots) but also more mixed. Indian and black areas are relatively homogeneous, with the exception of Newlands.

Indians have only five areas in the province which they form populations above 10%: Durban (24%), Newcastle (20%), Richard’s Bay (18%), Ladysmith (15%), Umhlali (15%).

Of these five, only four (Durban, Newcastle, Richards Bay, Umhlali) have a near even black-to-minority ratio. Ballito (formerly, “Dolphin Coast”) also falls under this category, but has only a 5.7% Indian population.

A similar pattern emerges for white people - several towns have a sizeable white plurality, and some little ones even have a white majority. But all of these towns are part of municipalities which include enormous black populations from the surrounding area, subjecting these communities to an overwhelming electoral defeat in every election.

There is little option for meaningful minority representation anywhere in the province. There is only one option to dilute the incumbent powers, but it suffers from a severe coordination issue.

The DA has made one abnormal gain, in uMngeni municipality, which is 75% black, and only 20% white. Their candidate Chris Pappas, a gay, Zulu-speaking Anglo of Greek descent, managed to draw in serious support with his on-the-ground campaigning in fluent Zulu.

The party has managed to make several serious gains in service delivery as a result of their 3-seat majority in the council, but unless they have another 50 or so white Zulus in their back pocket, the likelihood is that this will stall.

Besides, the addition of Chris Pappas, while it may have attracted the popularity of some black residents, seems to have only tipped the needle a few points - from 42% in 2016 to 47% in 2021. While the district is only 20% white, the voter turnout among whites as more than double that of black people in general, and so voter apathy is likely to be the main cause of the lead, however excited the DA’s PR division may be.

Battle Royale

One of the missed opportunities for the Zuma faction in 2021 was the untapped potential for Zulu nationalism.

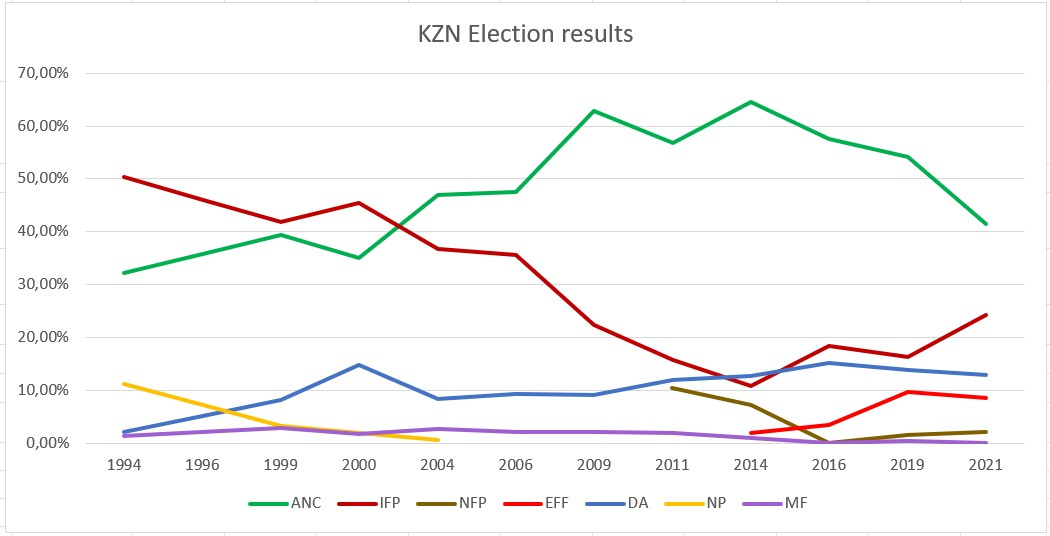

Zuma himself campaigned for the presidency on his ethnic background, under the famously controversial slogan “100% Zuluboy”. He became the first leader of the party in living memory who was not a Xhosa, and immediately sliced the Inkhata Freedom Party vote in half.

His capacity to manage perceptions of his corruption charges allowed him to cultivate the image of a persecuted man of the people, resuscitating accusations of Mandela and co being sell-outs, and of Mbeki selling the National Democratic Revolution down the river for a neoliberal policy model.

Nine years of stoking this image, as well as his background as the head of intelligance, meant that when it came to the crunch, he commanded the loyalty of the armed wing of the party, and leveraged their abilities to cause chaos in order to escape his jail sentence.

At the time, much of black Twitter got excited about idea of an independent Zulu kingdom, but the forces on the ground, instead of organising on ethnic lines, organised on racial lines, and pushed the black racial consciousness as the primary organising criterion, targeting white- and Indian-owned businesses and neighbourhoods.

By taking this stance, instead of galvanising the Zulu nation, Zuma discarded an opportunity to become father to a new nation, and instead will be remembered as a historical footnote, as a corrupt and slippery politician. His faction is defeated outside of the province, and many of his confederates are facing arrest.

That said, it would have been extraordinarily violent if he had taken such a stance, and would likely have resulted in a persistent violence for decades.

Since Zuma’s ousting, Ramaphosa has stepped up legal pressure on the Zulu Royal house, aiming to ultimately dissolve the Ngonyama Trust which runs the royal lands and holdings, an area roughly the size of Wales.

Zuma strengthened the powers and extended the recognition of traditional leaders across the country, including for the first time a number of tiny traditional Khoi and Griqua houses of the Cape.

Zuma’s efforts to take revenge have fallen rather flat. The African Transformation Movement, an ANC copy run by friends of the Zuma faction, has failed to achieve single digits, but in its infancy it was severely crippled by a massive infiltration paid for and organised by the late Jesse Duarte, which aimed to dissolve the party.

Similar shenanigans have split the Zulu vote, as ANC allies, the NFP have scooped up IFP votes only to hand their constituencies to the ANC. Like most things that happen in KwaZulu, the real arrangements are opaque, but easy to guess at.

Going underground

The main weakness of any party trying to oppose the ANC is that the minorities and the Zulu nationalists do not share constituencies for the most part. Looking at the municipalities with the largest minority demographics, we see very little of the IFP outside of Newcastle.

And in Newcastle itself, the IFP relies on the DA to achieve its governing majority, and cannot afford to see the municipalities redrawn to split the DA away from them.

For any minority who wishes to attain any degree of self-governance in the province, the only hope is to seek consolidation through non-political avenues - land trusts, neighbourhood watches, business compacts and legal funds.

But having little Afrikaner presence in the province, these groups cannot rely on Solidariteit or Afriforum in much more than a consultational role. They will have to do all of this by themselves.

The only hope is if the IFP and DA collectively get enough of the vote to form a coalition at the provincial level in 2024. This would require the two parties to get a 15% gain between them, which is unlikely but not entirely impossible.

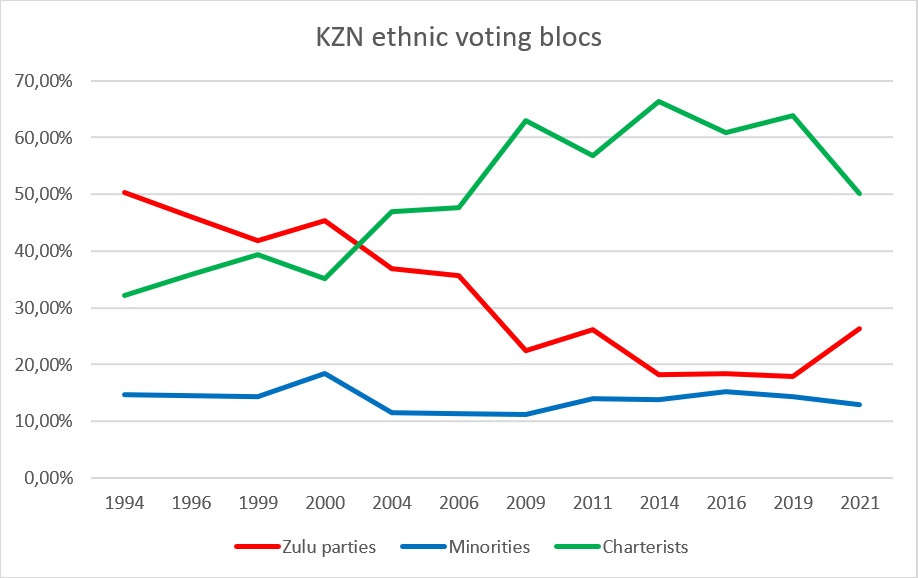

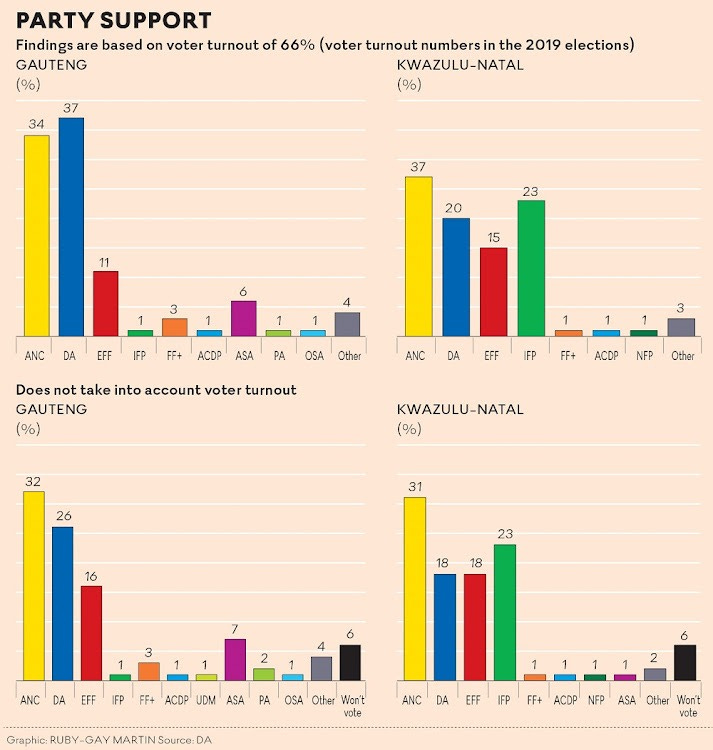

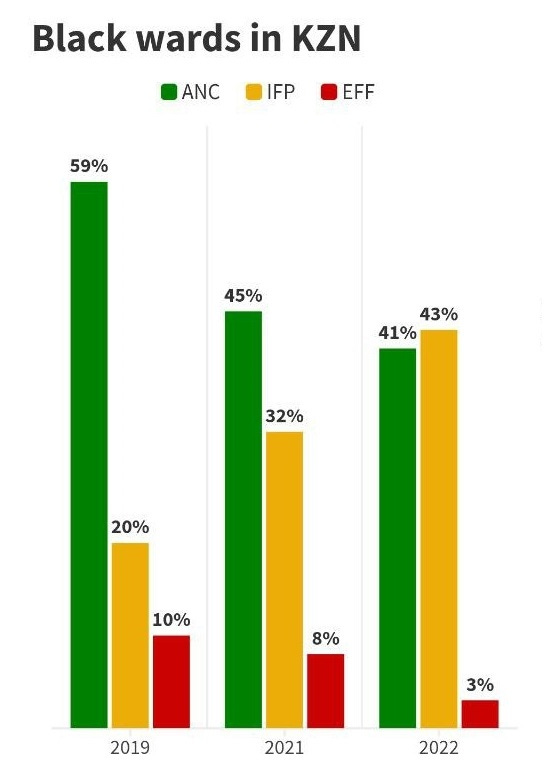

As the polling data (first graph) and byelections results (second graph - thanks to Dawie Scholtz) show, the IFP is poised to make a massive comeback next year, comparable to the early 90s, when they first dominated the province as the ANC’s main opposition.